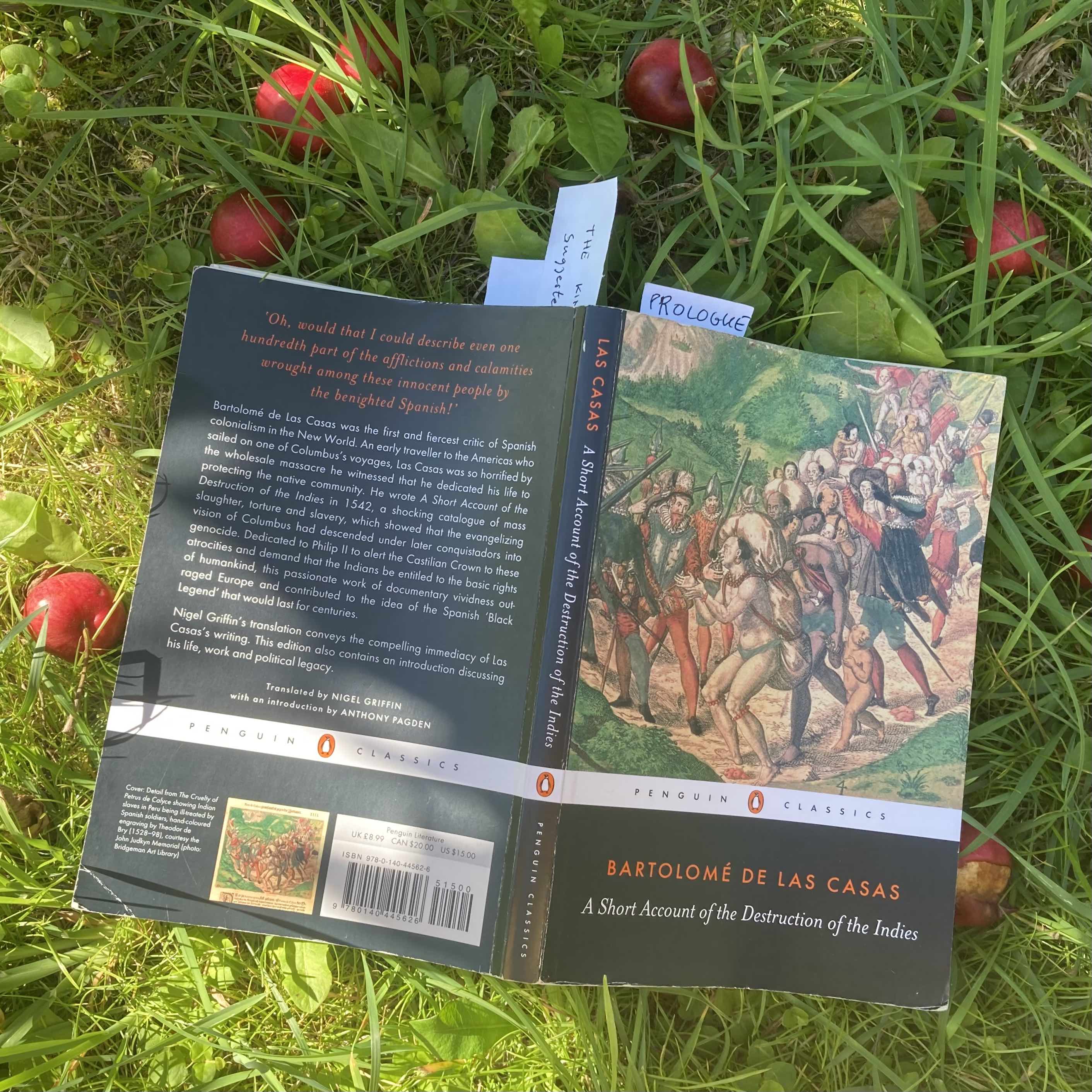

The Praxis study circle continues to inspire and inform my work with Mapping Praxis. By now, we’ve read a sequence of books from the 12th to the 16th centuries; texts that have mirrored and shaped the beginnings of modern-times’ colonialism. During the same period of time, a rapid development of mapping techniques took place, providing tools for the subjugation of non-European cultures and the following extraction of resources.

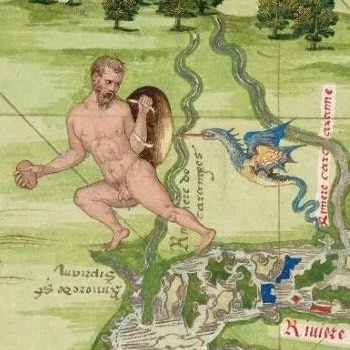

Guillaume le Testu’s 16th century map of Brazil (featured in the previous blogpost) pictures an archaic landscape where dragons dwell together with monkeys and other animals, and naked men are all at war with each other – sometimes molesting helpless victims, dismembering and burning them alive; a representation of indigenous peoples as blood-thirsty pre-humans in a paradise turned hell. There’s only one person sporting a dress (perhaps made from leaf foliage, following the example of Adam and Eve). She is the only woman depicted, and she also carries a crucifix as she strides confidently towards a naked, but seemingly grateful man… On the same map, the arrival of Europeans is marked by a ship with billowing sails at sea, and shining cities adorned with pennants along the coast. In reality, it was the Europeans wreaking havoc and committing genocide in the Americas as well as in Africa; le Testu’s visualization can be seen as pure and unashamed propaganda – a kind of pre-digital deepfake.

Today, the strive towards decolonialisation has sparked initiatives of counter-mapping / counter-cartography, in science and activism as well as in art.

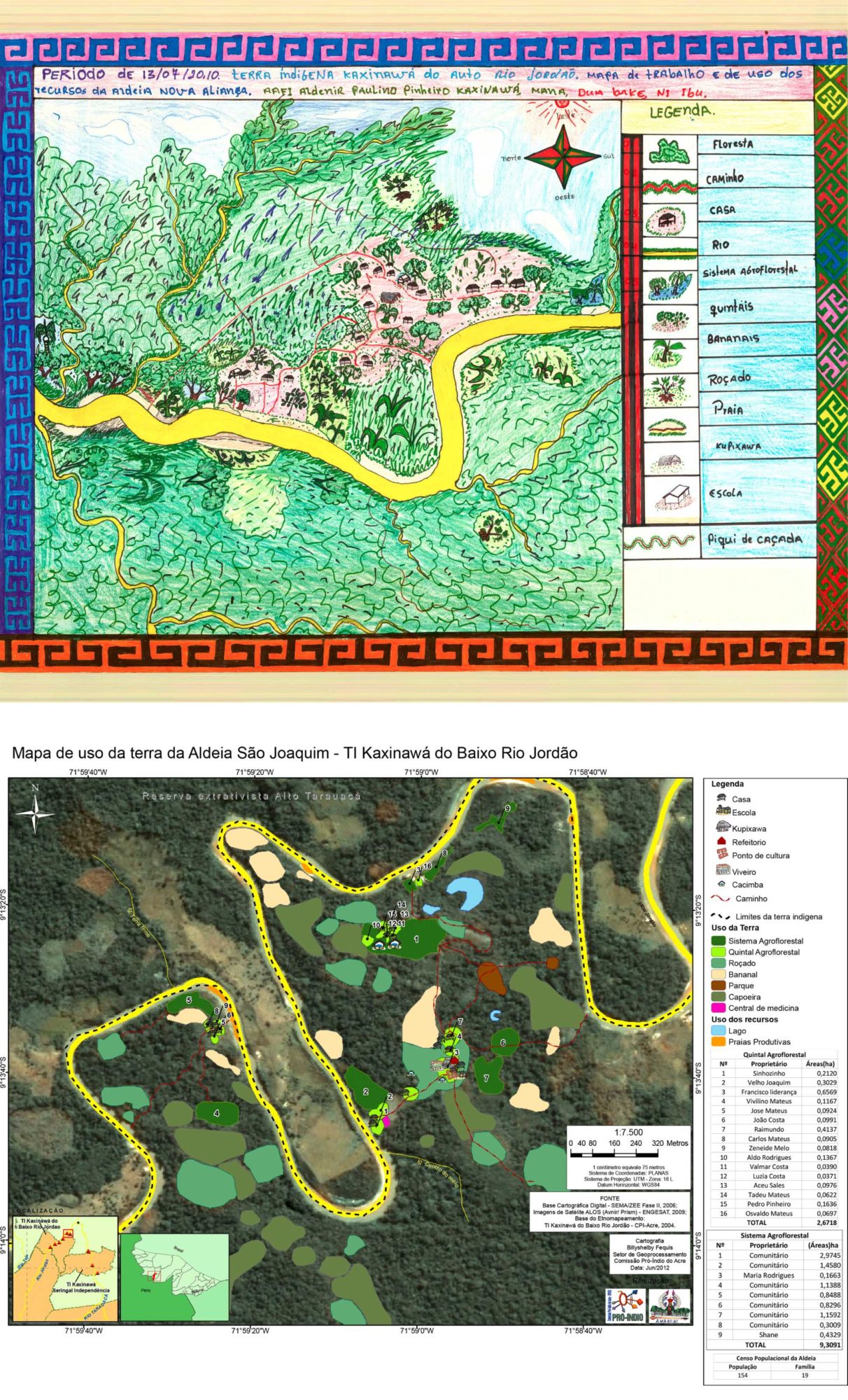

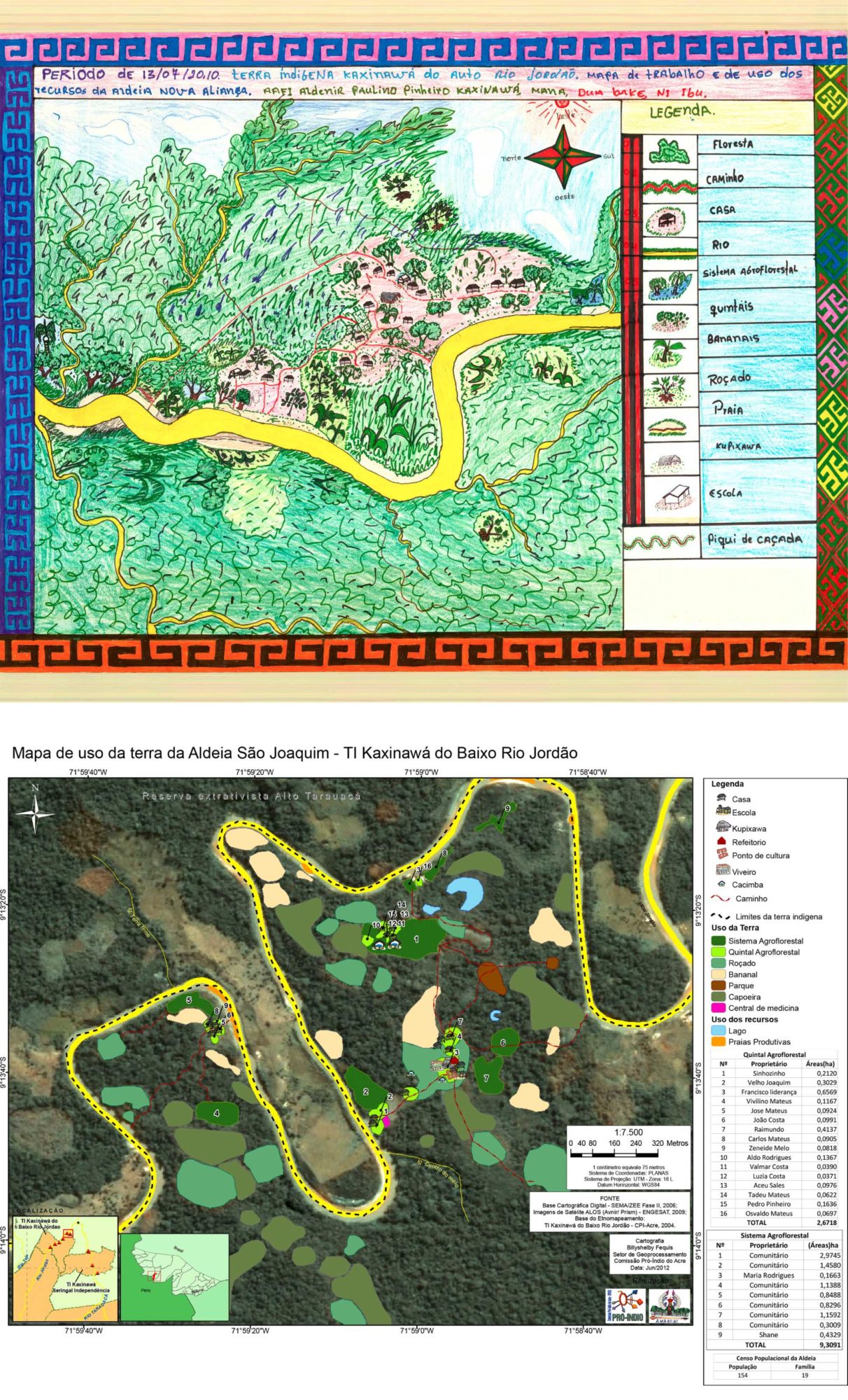

Two maps from ‘Indigenous Cartography in Acre. Influencing Public Policy in Brazil’ (via This Is Not An Atlas)

Two maps from ‘Indigenous Cartography in Acre. Influencing Public Policy in Brazil’ (via This Is Not An Atlas)

These are two contemporary maps from Brazil – part of the outstanding collection of counter-mappings known as This Is Not An Atlas by German kollektiv Orangotango. They are illustrations from a project by the organization Comissão Pró-Índio do Acre (the Pro-Indian Commission of Acre), which has been working since 1979 to support indigenous communities in the state of Acre. In contrast to a colonizer’s map, these ‘ethnomaps’ are tools for de-colonializing the mind as well as the land.

The ethnomaps made by indigenous communities are important planning tools for the protection, conservation and

management of natural resources. They fill the void of information found on official maps. They also expose

opinions, ideas and aesthetic preferences. Furthermore, they are a powerful tool that can be used for various

political purposes. The maps are also powerful tools to fight for certain claims. The production of ethnomaps

creates the possibility for indigenous peoples to build their knowledge and values on the Indian’s relationship with

‘the other’, thus contributing to the formulation of a future strategy by enabling non-indigenous people to

understand the processes of occupation of geographical space. It also sheds light on social interdependencies

within the economic, political and ecological contemporary world. In this case, the cartographic knowledge of and

for indigenous peoples can be an important advocacy tool within the territory and the cultural and intellectual

heritage it depicts.

Renato Gavazzi, Indigenous Cartography in Acre. Influencing Public Policy in Brazil

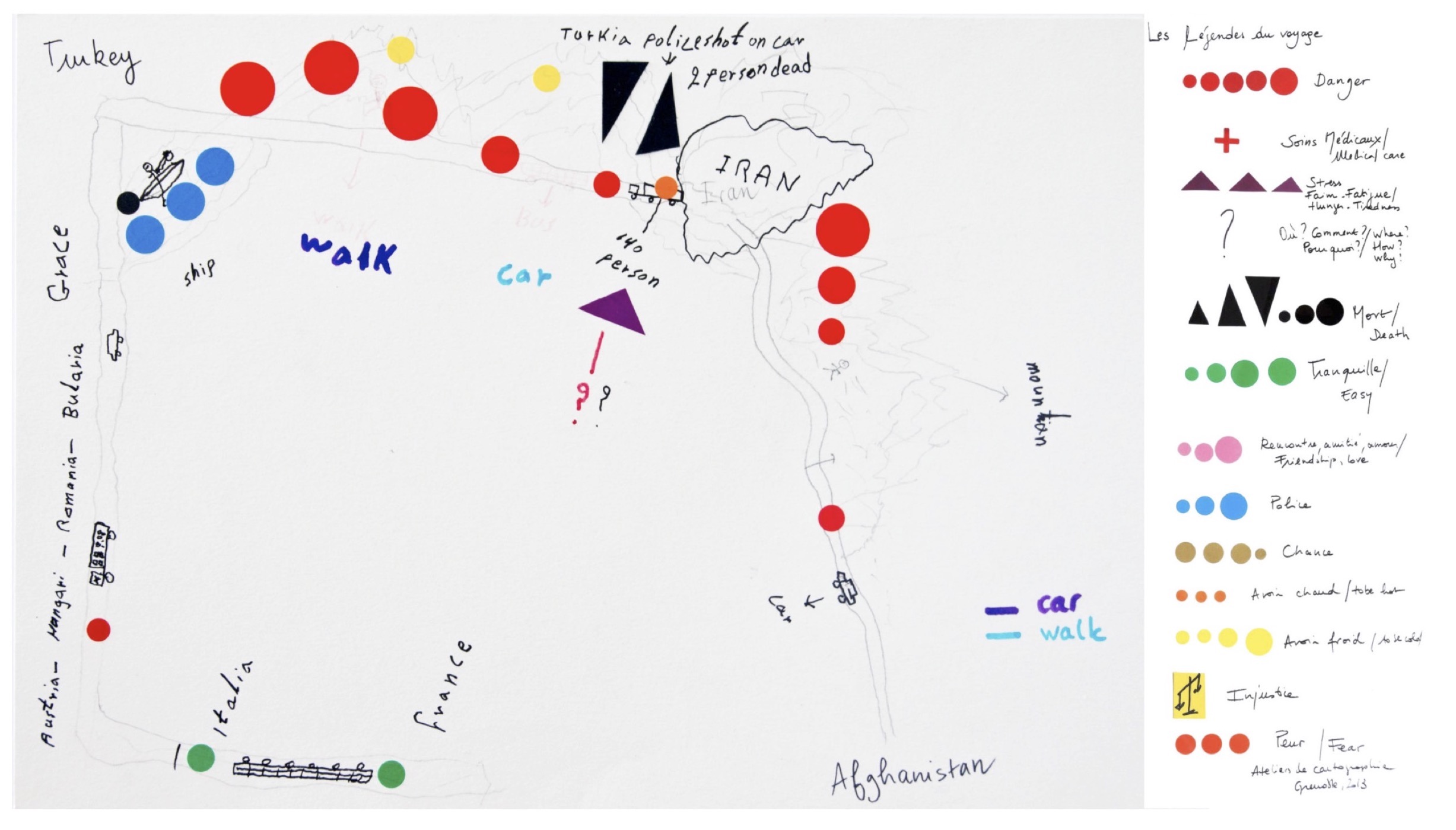

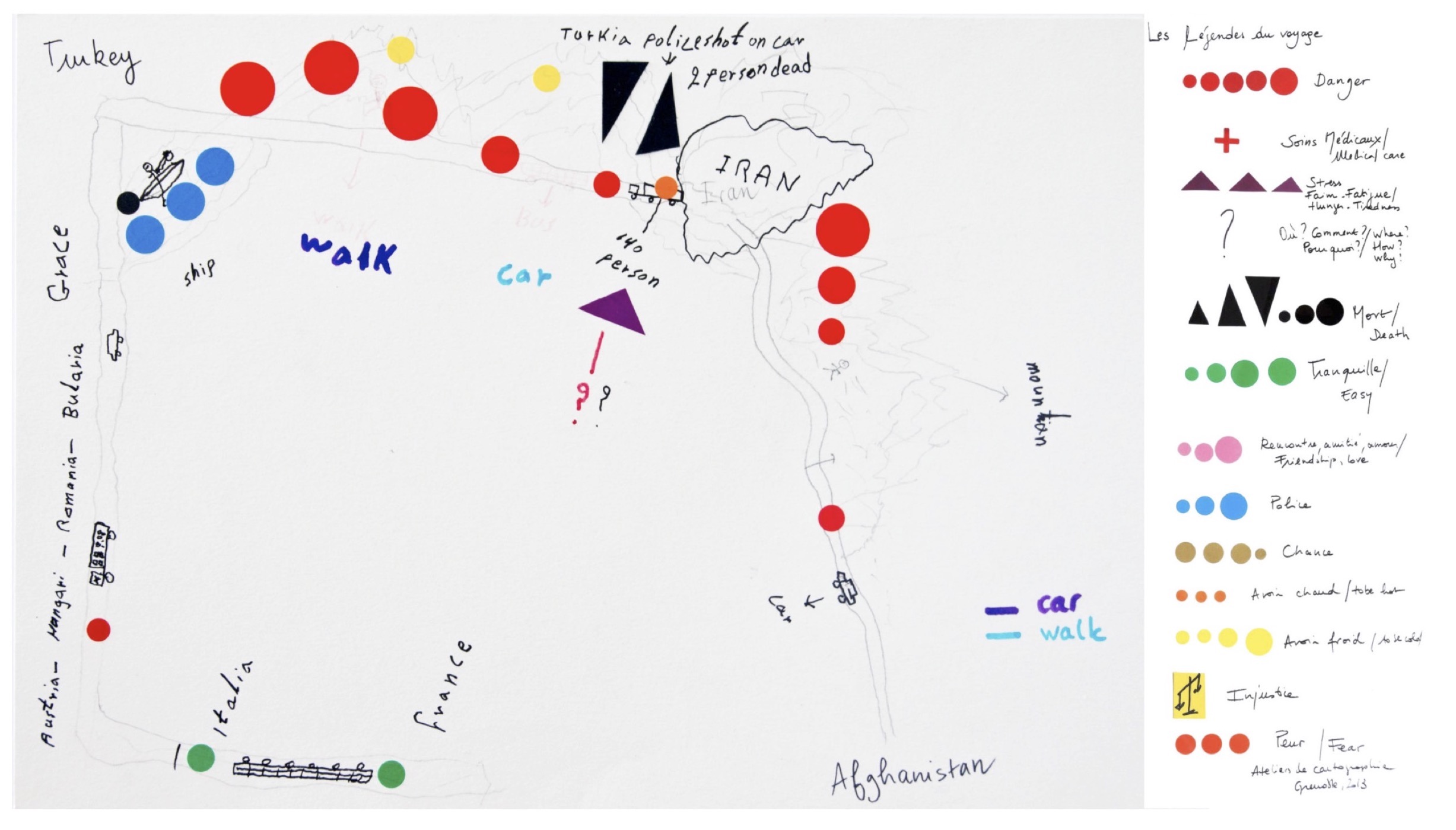

There’s a lot more to gather from the website of This Is Not An Atlas; especially, I’ve looked into The Counter Cartographies of Exile, a community project which took place in Grenoble (France) in 2013. It brought together thirteen asylum seekers, two geographers and three artists, using multi-disciplinary methodologies to bridge the divide between immediate experience and communicative skills. Starting out from the intention to open a creative space of hospitality, and to breach some cartographic norms of migratory representation, the project evolved over time. In the end, the maps came across as ‘trajectories of memory’ – neither true, nor false.

‘From Afghanistan to France; The Counter Cartographies of Exile’ (via This Is Not An Atlas)

From Afghanistan to France

The map presented here […] sketches a trail of exile from Afghanistan to France. It was created

by H.S*, who was seeking asylum in France when we met.

[…]

The map’s zenithal view makes it possible to understand the places and the distances involved at a glance, but it is

not the only perspective that is presented. The map is also drawn from ground level, using the path pursued, and

from inside the trailer behind a truck. In the frontal view, the mountains around Afghanistan and Iran break with

the zenithal perspective, and so do cars, trucks, boats and an individual on the road. Returning to ground level, one

perceives the space as a landscape of displacement for H.S., who represents himself in his work. This map blurs the

dichotomy between the map as a grid and as a route.

[…]

This map of exile is not the creation of a totalizing eye; it is also seen from below, from the walking point of view

and the multiple practices and tactics used to cross geopolitical borders. In this sense, From Afghanistan to France subverts the conventional and normative maps of migrations and nation states.

[…]

In addition, From Afghanistan to France is not only a cognitive or mental mapping. In order to read the map, it is

necessary to read the map legend (see map at the end of the article). Here the different symbols do not represent

rivers or settlements; instead, they symbolise the fear, danger, police, injustice, friendship, love… encountered en

route.

*The use of the initials has been decided by the person itself.

Counter Cartographies of Exile

The last section of this quote highlights the use of map legends (keys) as a visual meta-level; a means to clarify the context, the values and priorities of the mapper. This is something that I bring into the Mapping Praxis project – which also, by the way, is a process evolving through continued dialogue, deepening over time.

Assorted small objects; Mapping Praxis resources, work in progress

Two maps from ‘Indigenous Cartography in Acre. Influencing Public Policy in Brazil’ (via This Is Not An Atlas)

Two maps from ‘Indigenous Cartography in Acre. Influencing Public Policy in Brazil’ (via This Is Not An Atlas)